Decor Maine’s editor-in-cheif shares her shelter during the storm.

Designer Brewster Butterfield, Prospect Design

Builder + Cabinetmaker Papi & Romano

Interior Design James Light

Den Builtin Derek Preble

Custom Railing Nate Deyesso, DSO Creative Fabrication

Upstairs Flooring Atlantic Hardwoods

Tile Distinctive Tile

By Kathryn Williams

Photographed by Michael D. Wilson

As I arrive at Susan’s slate-gray three-story on Munjoy Hill, there is news on the radio of millions of Americans sheltering in place. California. New York. Maine not yet, but we won’t be far behind. The coronavirus pandemic that has swept the globe and now the country has breached the levees of Vacationland.

I don’t mean to be bleak, because this home is not bleak, nor is my visit—wherein my host and I stand at least six feet apart and I am reminded of a mother’s admonition to look with your eyes and not with your hands. I can’t accept Susan’s offer of tea, and she knows it, but this is just the gesture with which I want to begin this article. Because we are in an extraordinary time, and this house filled with family and art and letting go and new beginnings and thanking is wrapped up in the best of what this pandemic will come to mean to humanity.

This sounds overblown.

That is OK. Although she is my editor and although I know of Susan Grisanti, I do not presume to know her. And yet, she has welcomed me into her home. In some ways, she had to. This issue was supposed to feature the Cape Elizabeth home of photographer Jocelyn Lee, known for her psychological portraits and, more recently, natural still lifes, but the artist has come down with the flu in a time when illness is not taken lightly.

And so, Susan has decided to offer, for the first time, her own home to the reader. Only it’s not a great time for it. Last year, she bought a small cottage in Biddeford where she intends to move after renovations, and the house on the Hill is periodically rented, though not now, luckily, as two of her three children have returned from colleges closed for quarantine. Susan’s daughter sits at the dining room table where, just weeks before, her friends enjoyed a communal meal of lasagna and now she prepares for a videoconference with a professor 40 miles away.

Renovations included stripping horsehair plaster from walls and ceilings. All of the exposed joists, such as these in one of Susan’s daughters’ rooms, are functional.

It is clear that what feel like key elements of the house have been removed to Biddeford—the kind of personal effects one banishes for a real estate staging; some will return for the photo shoot, but the house has the feeling of an exhale. It’s not how I imagine someone who curates the art of shelter for a living might want to open her home to the public, in transition. There is a certain vulnerability that feels appropriate to this moment in time. “I always did intend to share it,” Susan says, but I hear an ellipsis, not a full stop. Later, when I ask again, “I’m nervous,” she admits. “It is nerve-racking.”

Susan bought the home in 2013, at a time when the controversial gentrification of the “Old Hill” was reaching its apex. Constructed in 1844, the structure was originally a two-family home subdivided into apartments. It had fallen into serious disrepair, its previous owner unable to care for it. The house was rotting. In her naïveté, Susan admits, this was what she was looking for. “I wanted a blank slate.” Nearly a year and a half of renovations later, on Christmas Eve 2014, she moved in.

“When we moved here, it was a salve to my wounds,” says Susan, perched at the distant end of a Calacatta marble–topped island in a sea of cabinetry painted in Benjamin Moore’s Black Ink. After four years in the Cape Elizabeth home she’d shared with her ex-husband, a decision she appreciated for the “steadiness” it allowed her children, the self-described introvert was ready to be in the city. “I can live like a little mouse in this house,” she says, “but I [also] wanted to be around people.”

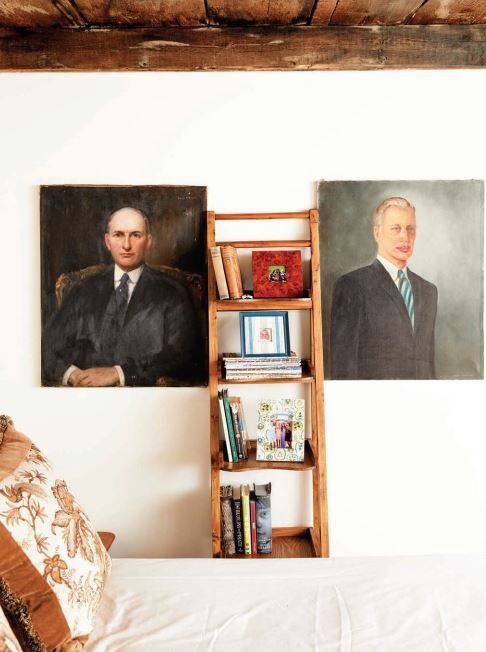

And art. A lot of it. This is the lens through which Susan tours the house. It’s the theme of this magazine issue, but I get the feeling it’s the way she’d always show her home if possible. A collector of contemporary art, especially from Maine artists, she owns 26 pieces. The first she shares, titled The Next Step by printmaker Sissy Buck, graces the hallway between kitchen and den, an appropriately transitional space for a piece that spoke to Susan at a Maine College of Art sale as her marriage was falling away. She traces the movement of the line drawing with her finger. “I looked at it and understood exactly what she was saying.” There is a Robert Indiana, signed four times, in the living room; a photograph by Melonie Bennett, of a tattooed, bustier-clad woman dancing, in the powder room. The Lesia Sochor above Susan’s desk explores the female form as mannequin. Up a soft swoop of staircase, three stark black-and-white works establish the home’s neutral palette, while in the attic-turned-third-floor-master-bedroom, a Will Barnet print pops joyfully behind a custom steel railing by Nate Deyesso of DSO Creative. When I ask if Susan herself is an artist, she smiles, the same smile you’ve seen in her headshot. “I feel like putting this house together is my art.” With delight,

For the kitchen, Susan chose modern blue-based black cabinetry with builder Rick Romano and brassy details, as in the range hood and bar counter from Rusted Puffin Metal Works of Portland. opposite page The dining room table was purchased from former Rockport gallerist Edith Caldwell, who’d had it custom made. For years, it’s hosted family gatherings—and, hopefully, soon friends again.

she shows me the integrated door pulls carved into a white oak bathroom vanity. “That’s wood sculpture,” she marvels. There were many mornings, before her children woke, that Susan would sit on the grass-green velvet of her couch simply staring into art and space. I wonder aloud what she makes of the current panic. “I [have] had the bottom drop out on me,” says Susan. “We survive really hard things…. I’m not being Pollyanna, but I really feel grateful.”

All over the world, people are entering into new relationships with their homes. One hour, they are prisons. The next, they are shelter at its most primitive, a calm harbor in the storm. Across from the grass-green couch hangs an Alison Hildreth panel, the artist’s ink wash on rice paper a gray-sulfur mythical coastline titled Navigation.

Susan’s next house, the 900-square-foot cottage in Biddeford, she describes as like a little boat. “It’s refreshing to live like that, with just what you need,” she says. There is something Susan says, shortly before I leave her home, Purell drying on my hands. It is about the pandemic and its effects: There is a reckoning coming; it is not without its joys.

“The palette was always black, white, gray, and brown. Then I started bringing in color,” says Susan. Above the bed is a painting of Union River Bay by Lisa Creed. right A salvaged door with a painted ladies room sign came from Nobleboro Antique Exchange. The bathroom walls are in Champion Cobalt from Benjamin Moore. below Room with a view—a photograph by Cig Harvey above the vintage claw-foot tub in a small second-floor bath offers the illusion of space.”